Legacy Keepers: The Atlanta 1906 Race Riot

By 1900 the population of Atlanta had more than doubled to 89,872 from its 1880 level including the black population that quadrupled. This increase led to increased job competition and white politicians responded as they had during slavery by implementing and expanding Jim Crow. These laws included segregated neighborhoods, public transportation, and schools. Despite these hurdles, black excellence persisted. By this time three black colleges were created in Atlanta and a small number of black families achieved a significant measure of success. Black men continued to exercise the vote they gained during Reconstruction. African American activism and the growing black middle class made many whites uncomfortable.

The 1906 gubernatorial campaign added fuel to the racial fire, as both, Hoke Smith and Clark Howell, advocated disenfranchisement of all black voters in rivaling newspapers, the Atlanta Journal, and the Atlanta Constitution.

Both men capitalized on white citizens fear of crime rates and the perceived threat of black men against white women. On September 22, after four alleged sexual attacks on white women by black men were reported in the local white press, a mob of approximately 10,000 white men formed downtown. The mob surged through black Atlanta neighborhoods destroying businesses and assaulting hundreds of black men.

The violence became so dangerous that the state militia was called in to take control of the city. Still, some white groups persisted in attacking black neighborhoods, and black men organized to defend their homes and families on the campus of Atlanta University. Led by educator, sociologism, civil rights activist, and Pan-Africanist, W.E.B. Dubois and his shot gun, those who could make it took refuge inside North Hall, renamed Fountain Hall by Morris Brown College is currently being refurbished.

Georgia Encyclopedia estimates the number of blacks killed between 25 and 40 while two white Americans were killed. Hundreds more people were injured or saw businesses and homes destroyed.

News of the riot spread across the globe and threatened Henry Grady’s illusion of “the New South” and the economic stability of the region. According to Grady, “The old South rested everything on slavery and agriculture, unconscious that these could neither give nor maintain healthy growth. The South’s perfect democracy, the oligarchs leading in the popular movement; a social system compact and closely knitted, less splendid on the surface, but stronger at the core; a hundred farms for every plantation, fifty homes for every palace; and a diversified industry that meets the complex needs of this complex age.”

White leaders reached out to the black elite, to negotiate a peace. These meetings set the stage for the Atlanta Way.

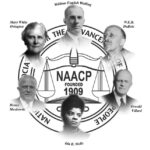

Following the Atlanta riot and other riots across he country, W.E.B. Dubois a founding member of the Niagara Movement, left that movement to form the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and The Crisis. Originally subtitled, “A Record of the Darker Races,” The Crisis was a groundbreaking outlet for discussing critical issues confronting the African American community and sharing the intellectual and artistic work of people of color.

Walter White was just a boy when his family was forced to flee Atlanta’s Old Fourth Ward to during the riot. Taking advantage of his fair complexion, White worked for the NAACP posing undercover in the investigation of 41 lynchings, 8 race riots, and two cases of widespread peonage. These activities set the backdrop for a young Martin Luther King Jr. and other Blacks who turned away from the previously popular teachings of Booker T. Washington in favor of more assertive approaches to civil rights.